On Microservices (Chapter 7 - Verb Services)

4 of 4 - Verb Services

For reference, the 4 service types were:

- Noun

- Query

- Journal Reader

- Verb

— Verb Services —

The last of the 4 service types yet to be discussed is Verb Services.

Verb services mostly exist to expose simplified APIs.

One could argue that Verb Services are mostly just a pattern, but in practice this is usually not the case.

Without fail, Verb Services end up sharing a significant amount of code with the other services as you standardize how all of them are written. Things like:

- how outbound calls are made

- how security (authn and authz) is implemented

- the presence of standard monitoring interfaces like “Ping” and “HealthCheck”

- etc.

Before you are done, they end up as clones of Noun Services sans the ‘Resource’ and ‘Journal’ tables.

Here is an example from (where else?) the world of commerce:

Let’s say you have all of:

- a product catalog (what you sell - offers with pricing rules)

- a recommendation system (creates up-sell/cross-sell recommendations for customers based on purchase history, where they live, etc.)

- a discount system (creates discounts for buyers based on loyalty plan memberships, etc.)

It is common to make each of these into separate services that can be used standalone. It can also be wise to establish differing SLAs (service level agreements) for each. For example, perhaps the product catalog and the discount system must ALWAYS be up to enable sales. But is your business willing to block potential sales if the recommendation system is down or slow?

Unlikely.

Aggregated GETs via Verb Services

Having a verb service sitting in front of all three can be simplifying, a la:

- It can offer a single API for front-end apps to call that intercedes with the 3 services behind it to produce a single result containing:

- a fully priced and discounted offer

- an optional set of recommendations for up/cross selling as well

- The verb service does the fanout calling of the background services in whatever order makes sense.

- The verb service knows how to combine the results into a nicely formatted response for the front-end caller

- The verb service knows that it does not have to wait for the recommendations response if, for some reason, that response is slow

- None of the backend services called by the verb service need to call each other or even know the others exist. (separation of concerns is a beautiful thing!)

- It is faster, simpler, and less error-prone to do the multiple calls from a verb service running side-by-side with the other services than from the front-end

Coordinated Updates via Verb Services

Verb services can also be used to coordinate updates spanning multiple backend services. A version of this is a verb service offering a single interface that, when called, makes multiple backend calls to do related updates..

This coordinated update pattern can also be extended to add protections not found in backend systems (e.g. legacy code).

-

For example, a verb service could expose an API that offers idempotent updates (double call protection) in front of multiple services that do not implement idempotency.

A contrived example to illustrate this might be a debit in one system followed by a credit in another. Having a verb service sitting between a caller and multiple backends that need to be updated in sync, and which helps prevent mismatched updates, can reduce system headaches in a big way.

This is useful for safely repeating calls without fear of doubling up on the debit or credit calls if a connection is lost prior to the caller receiving a response.

NOTE: Depending on whether or not the downstream apps called provide for a GET call to see if their part of the coordinated update has occurred or not, the Verb Service in question may be required to have its own storage to record partial progress. At this point you have essentially crossed back over into the realm of a noun service, where the noun in question is the coordinated operation itself.

Gateway Services via Verb Services Another common use of verb services is to build API (or protocol) translators that bridge between disparate systems. The world of B2B APIs often requires such.

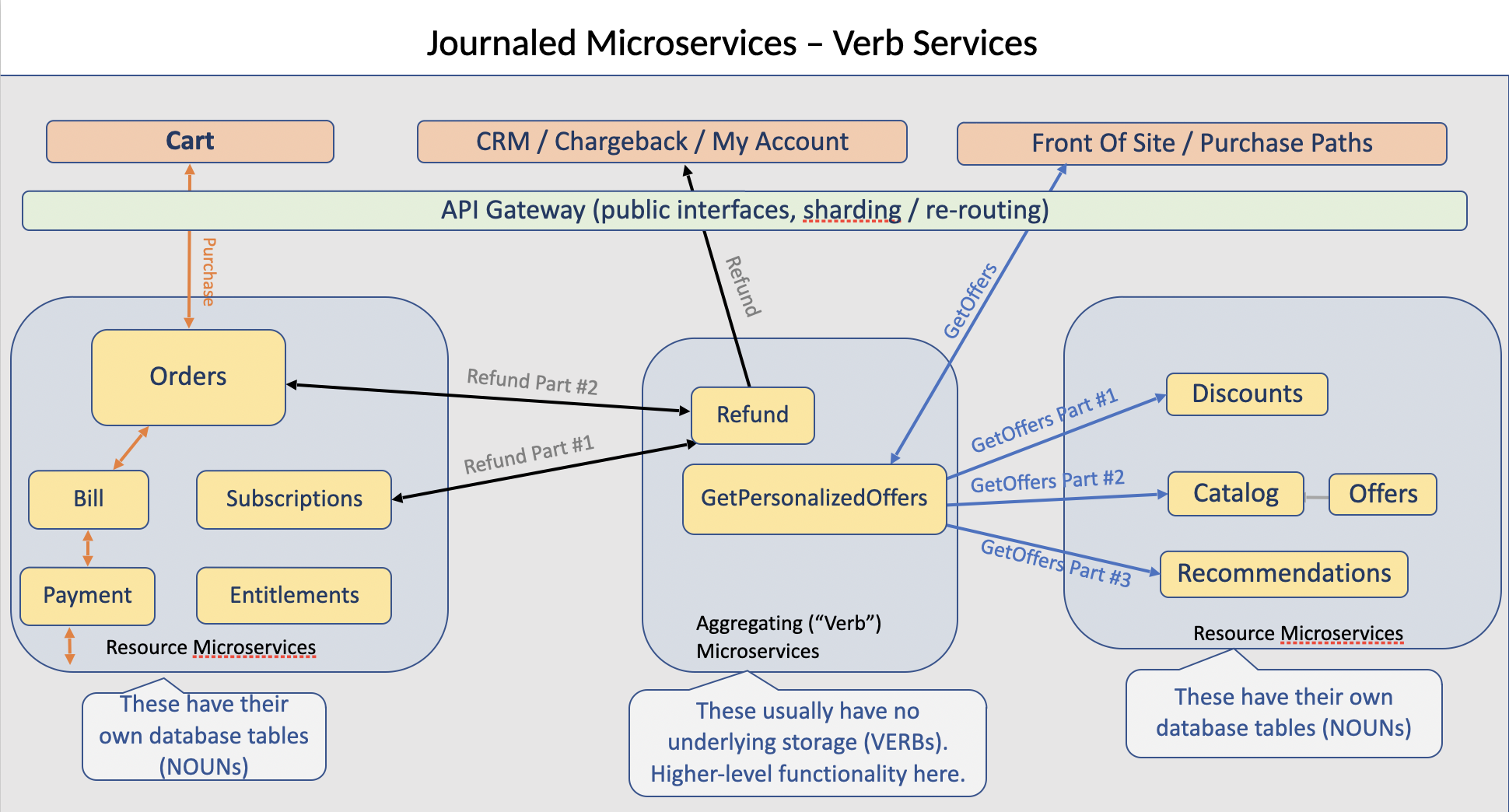

Here is a depiction of the first two scenarios mentioned above:

That is pretty much the extent of verb services. Very useful, but also simple.

It also completes the discussion of the four type of services in the Journaled Microservice architecture.

A quick note before I summarize:

Have you noticed that the entire journaled services model requires absolutely nothing that is only available from cloud vendors?

Being cloud-agnostic is empowering for your company, not the rich cloud vendors.

Perhaps this is why none of them offer something this simple? LOL. Dumb conspiracy theories aside, it should be clear by now that the journaled microservice model helps you spend less money on cloud services and avoids lock-in with any particular cloud vendor or usage of the cloud at all.

Want to run it all in your on-prem data center? Go for it.

Unlike most of what I have shared here, this cloud-agnosticism goal was not a concern for the original Microsoft team (they used Azure, duh), but for many of us who subsequently used journaled microservices outside of Microsoft, it definitely has been a goal, and staying true to that goal has been very empowering.

I’ve run entire apps built using the journaled services model on a laptop. For testing, I’ve configured services spanning my laptop, on-prem data centers, and cloud services (all working together).

The point is that you have control to do whatever makes sense for you.

Ok, now for that summary.