On Microservices (Chapter 3 - Noun Services)

1 of 4 - Noun Services

So, what were the 4 service types?

- Noun

- Query

- Journal Reader

- Verb

This chapter will examine the first.

— Noun Services —

In REST-speak, these are resources. (I’ll sometimes use them as synonyms herein.)

Common examples are Orders, Payments, Subscriptions, Entitlements, Customers, ServiceRequests, Questionnaires, Answers, Chats, ScheduledJobs, etc.

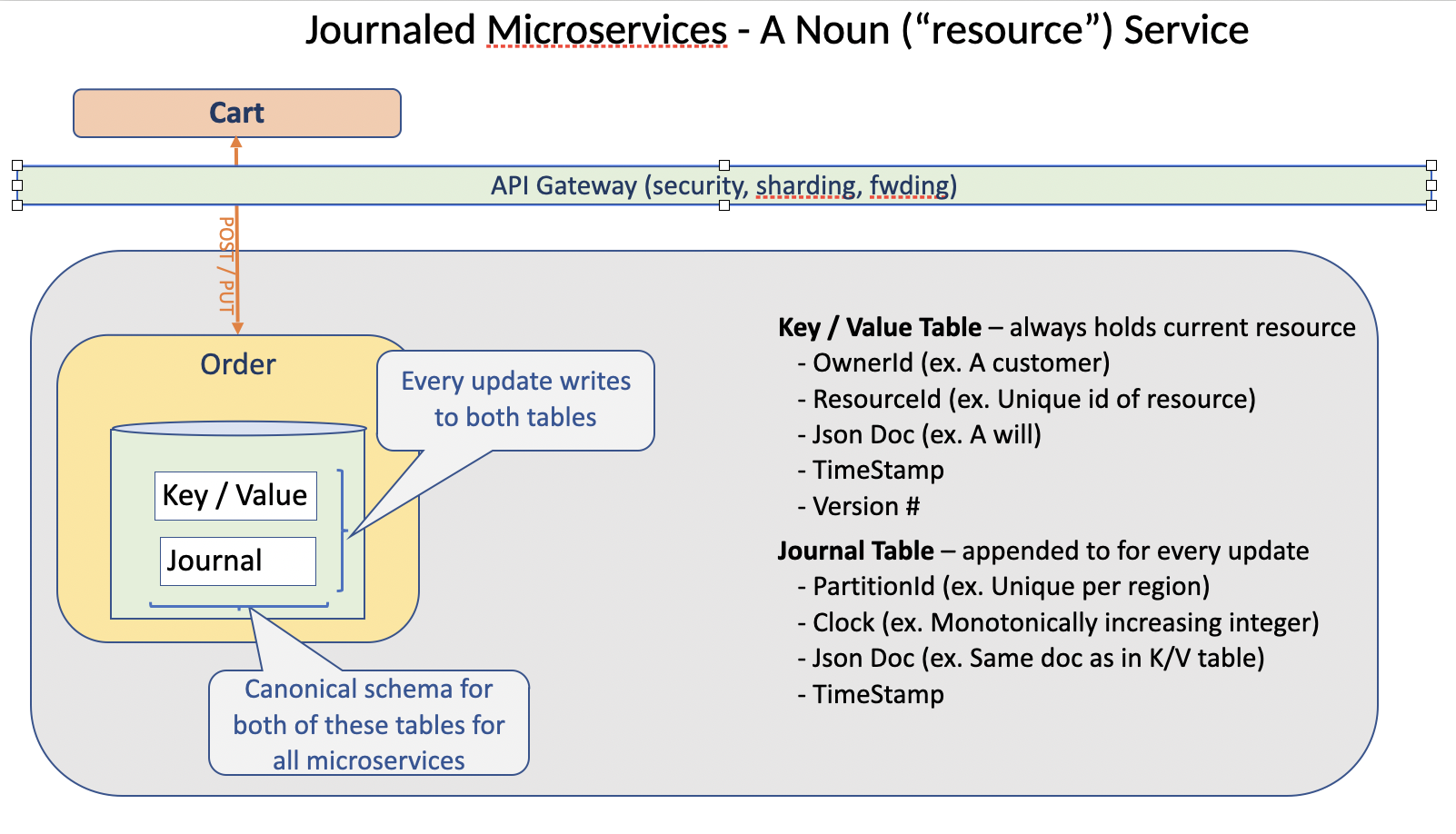

A key (and simple) innovation that the Microsoft team contributed was to make their nouns “Journaled”.

In a noun service, every ‘write’ stores the latest version of a resource in an identity-keyed ‘Resource’ table while also appending the latest version of the resource into a ‘Journal’ table as part of the same ACID transaction.

This creates an in-order ledger (history) for each instantiated resource. The journal is useful for:

- other loose-coupled apps/services to monitor to launch work of their own

- populating both data-ponds (operational) and data-lakes (analytics)

- replay/recovery

- compliance with SOC 2 requirements

Noun services typically support the REST verbs: Get, Post, Put, Delete, etc.

While Get (Resource By Id) and Get (Resources By Owner) are supported, what you will not find in noun services is support for all sorts of random GETs filtering across resources with (in SQL terms) a variety of WHERE clauses.

As mentioned earlier, the architecture team noticed in many cases that these sorts of GETs often grew to dominate the writing and maintenance of many noun services. Another takeaway was that these queries rarely, if ever, needed to be done as part of the natural lifecycle of a resource (ie. when it was created, modified, or deleted).

Further, supporting such filtered GETs typically prompted “shredding” of an (e.g. JSON) object into multiple tables with their own indexes on write operations, and also necessitated complicated joins to reconstitute an object for a GET.

I’ll note here (again, for emphasis) that app-specific database calls in edge-callable services are where most SQL injection attacks occur.

With all of that going against them, the filtered GETs were removed. To be more precise, they were relocated elsewhere. More on that later.

By removing filtered GETs logic from noun services:

- the JSON payload could be stored without being serialized to mutiple, app-specifc tables. In fact, the only two tables required were the above-mentioned resource and journal tables, which have standard schemas.

- the usage of ORMs (and/or custom database logic or both) in noun services was eliminated entirely because it was no longer needed (I suspect the angels sang).

Instead:

- noun services used a standard resource database library to do the simple work of storing and retrieving a resource in JSON form

- JSON objects were stored in a column as text (nope, not even those cool JSON columns were used because they were slower).

- Due to simply storing the object in JSON form and the elimination of filtered GET support, the average number of writes (tables+indexes) was reduced - usually significantly.

- Support for optimistic locking, an important but often overlooked feature, was added for the benefit of all noun services in the resource library as well.

In essence, they morphed the definition of a microservice from:

- “single-focused piece of code that has its own database”

to

- “single-focused, journaled piece of code that is wholly contained in two standardized tables”

That doesn’t roll off the tongue quite so easily, but to quote Einstein, “things should be as simple as possible, but not simpler”.

Albert would have been proud because noun services became faster, consumed fewer resources, and were simpler to scale due to predictable (and less) database usage. Plus, writing & maintaining them became much simpler, too.

Next up: Query Services